Q+A: Adam Hollowell and Keisha Bentley-Edwards

Dr. Adam Hollowell serves as Senior Research Associate at the Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity and Director of the Inequality Studies Minor at Duke University. He is also the Faculty Director of the Benjamin N. Duke Memorial Scholarship Program and Director of the Global Inequality Research Initiative. An award-winning educator, he teaches ethics and inequality studies across multiple departments at Duke University, including the Kenan Institute for Ethics, the Program in Education, the Department of History, and the Sanford School of Public Policy.

Dr. Keisha Bentley-Edwards is the Associate Director of Research and Director of the Health Equity Working Group for the Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity and an Associate Professor of Medicine, Division of General Internal Medicine, at Duke University. She holds several leadership positions within Duke’s Clinical and Translational Science Institute, and faculty affiliations with Duke’s Global Health and Cancer Institutes.

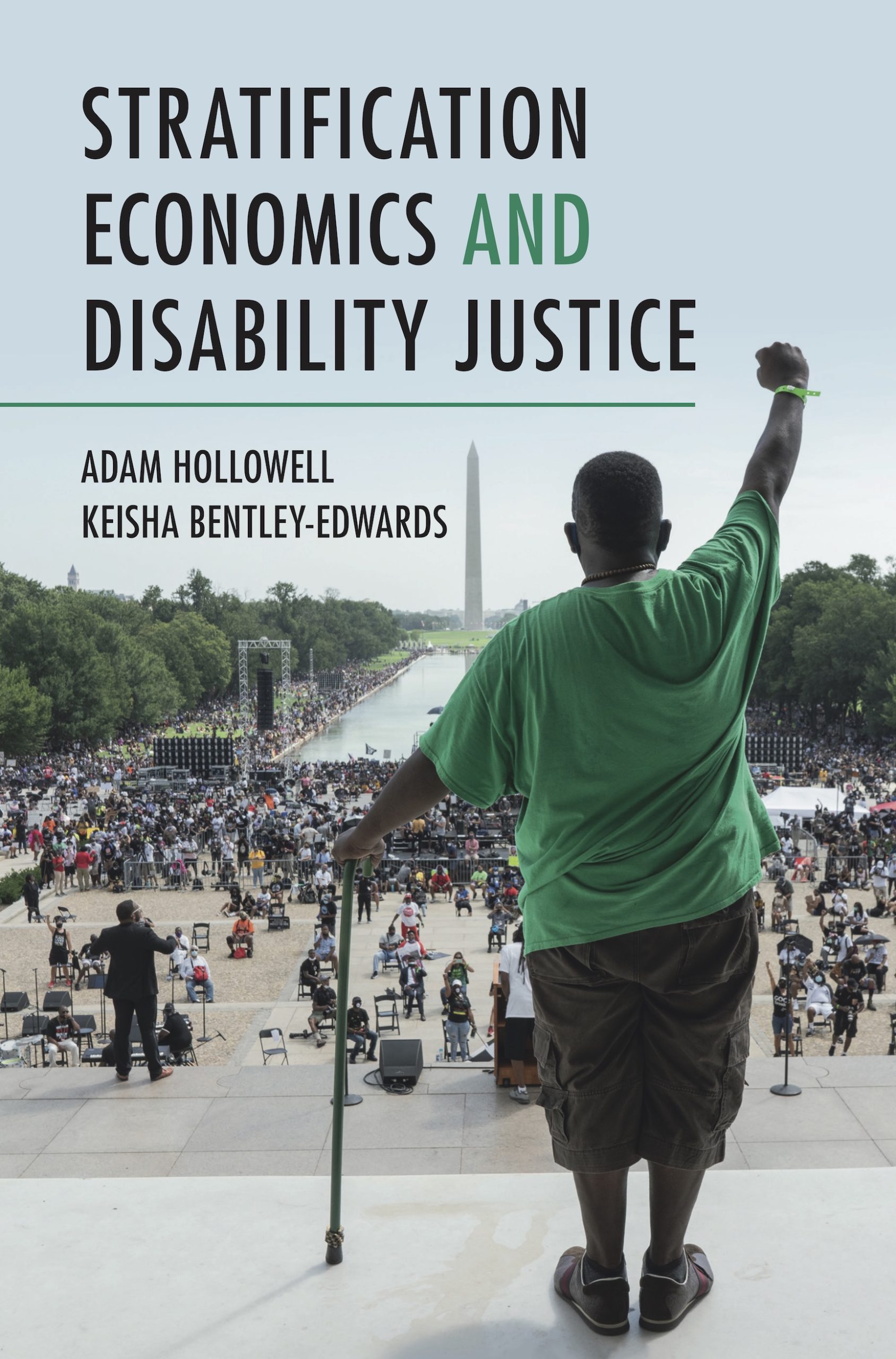

In this Q&A with Cook Center research associates Rachel Ruff and Lucas Hubbard, Drs. Hollowell and Bentley-Edwards discuss their experience working on their recent co-authored book, Stratification Economics and Disability Justice (Cambridge University Press).

Q: What was your motivation for this project, and how did the two of you come together to work on this?

Adam Hollowell: In 2016, I came across a statement from the Harriet Tubman Collective, a group of Black disabled organizers, called Disability Solidarity: Completing the “Vision for Black Lives.” The statement lamented the erasure of Black disabled people from groups affiliated with Black Lives Matter and called for “intentional centering” of Black disabled people in movement leadership. The Harriet Tubman Collective’s statement was signed by activists and organizers whose work I’d never encountered: Patty Berne, Dustin Gibson, Cyree Jarelle Johnson, Talila A. Lewis, Leroy F. Moore, Jr., Vilissa Thompson, and others. I have spent the better part of a decade following their work, listening to their words, and attempting to learn from their wisdom.

In 2019, I’d just completed my first year at Duke’s Cook Center on Social Equity, where Keisha was Associate Director of Research, and together we were leading a Story Plus summer program for the John Hope Franklin Humanities Institute. During that time, we discussed writing a book together. Keisha has been conducting health and education research using intersectionality for more than two decades. In recent years I have taught about disability justice and intersectionality in courses like How to Study Inequality and Global Inequality Research. We were both surrounded by work in the field of stratification economics emerging from the Cook Center. Eventually we decided to bring these ideas together into a single project.

And this book is the result.

Q: Your book ties together the two key concepts in the title: disability justice and stratification economics. Could you define these terms and explain their importance?

Keisha Bentley-Edwards: To quote Patty Berne, one of the organizers of the arts and justice collective Sins Invalid, “Disability justice is a movement towards a world in which every body and mind is known as beautiful.” Really, the concept arose in response to the disability rights movement, which worked to pass legislation against disability-based discrimination in the United States. This organizing was dominated by white leadership, and disability justice arose from communities that emphasized queer, nonwhite leadership and explicitly claimed intersectionality.

For instance, intersectionality is the first of 10 Principles of Disability Justice identified by Sins Invalid. “Ableism, coupled with white supremacy, supported by capitalism, underscored by heteropatriarchy, has rendered the vast majority of the world ‘invalid,’” the statement declares. Disability justice is, at every turn, a call for collective liberation.

Adam: Stratification is another word for divisions by group. Stratification economics is a branch of economic theory that aims to understand those divisions, why they exist, and, ideally, how to address them.

It’s useful to view stratification economics as a response to traditional economic theory. Classical economists explain some stark inequalities—for example, that in 2022 white families in the United States had about $260,000 more in average retirement savings than both Black and Hispanic families—as outcomes of individual preferences. The question stratification economists raise is: If economic preferences are individual, how do we end up with such rigid distributions of money, power, and status by group?

While stratification economics has explored group-based inequalities for a number of categories—caste, race, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, religious group, and language group—discussion of disability as a basis for group-based economic differences has largely been ignored, until now.

Q: The book centers and builds upon long-established efforts and advocacy from disability justice activists. How were their efforts a guide and an inspiration in the writing of this book?

Keisha: Both Adam and I have been teaching and talking about disability, inequality, and intersectionality for a number of years. But the lessons and teachings of these activists inspired and compelled us to take our research and teaching further. Disability justice focuses explicitly on overlapping movements for justice, so following their work pushed us to think about how stratification economics accounts for overlapping forces of inequality.

We begin each chapter of our book with a profile of a disabled Black activist who has worked for disability justice and describe their vision for a more just world. All academics are required to “show their work,” of course, but we want anyone who reads any part of the book to know where the core ideas originated. We want to invite readers into the world of disability justice through some of its most courageous and compelling leaders: Johnnie Lacy, Lateef McLeod, Cara Page, Angel Love Miles, and Brad Lomax.

Q: This book is the culmination of a lengthy writing and review process. How has the feedback you received underscored the importance of this work?

Adam: Stratification Economics and Disability Justice is the result of six years of writing together, from those conversations in summer 2019 all the way to publication day this month in 2025. Co-writing over that time developed its own rhythm: I’d draft a section and send it to Keisha, who would add research and insights, highlight gaps, and send it back to me for another round. We did this over and over, each pass clarifying the aims and arguments of the book. Of course, the book also underwent anonymous peer review from two economists, who critiqued the arguments and pressed us for additional evidence. Peer review is challenging, but it’s also always rewarding, because the manuscript is improved through rigorous scrutiny. Once we completed the peer review process, we hired a whip-smart (and unfailingly kind) editor, Jana Reiss, to guarantee that the book had one voice, from start to finish, even with two authors.

Q: Relatedly, what is the benefit of having a book written by two academics like yourselves, who might prompt different audience reactions than a book by advocates and activists?

Keisha: We wrote this book for economists, sociologists, and other researchers who study persistent inequality and social equity. The benefit to this approach is that we can speak their language, presenting empirical data, contemporary research, and persuasive arguments to make our case. It allows us to make a case that is convincing in (relatively) traditional economic terms.

The downside of this approach is that academic writing can be inaccessible—indecipherable jargon, absurdly high price points, exclusionary institutions. That’s why were quick to recommend non-academic books that share our commitment to disability justice and racial justice: Shayda Kafai’s Crip Kinship, Alice Wong’s Disability Visibility, LeRoy Moore’s Black Disabled Ancestors, just to name a few.

Q: Two major universal policy proposals that the book highlights are a Federal Jobs Guarantee and Baby Bonds, which Cook Center researchers have been essential in developing in recent years. Could you give an example of the importance of centering a disability justice framework in advancing these policies?

Adam: Let’s take proposals for a Federal Jobs Guarantee, which would ensure a government-provided job for every American over the age of eighteen. These proposals often refer, historically, to similar legislation enacted by President Franklin Roosevelt during the Great Depression, when the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and other agencies employed American workers for infrastructure and public works projects.

Many contemporary FJG proposals explicitly include protections for disabled workers in federal jobs, partly as a lesson learned from the exclusion of workers with disabilities from Roosevelt’s WPA. However, exceedingly few contemporary FJG proposals include disability access among the priorities of the infrastructure and public works projects at the heart of the program. For instance, Congresswoman Ayana Pressley’s February 2021 jobs guarantee resolution included a Workers Bill of Rights with accommodations for disabled workers, but it provided few details for ensuring equal protection under and participation in FJG employment. Additionally, disability access was absent from the goals of the public works projects.

For decades disabled activists have outlined specific proposals for universal design public infrastructure. Common demands include: increased accessibility in public housing, accessible polling places for voters with disabilities, and transportation upgrades making buses, trains, and subways more disability accessible. Advancing disability justice in a FJG program requires more than a few non-discrimination clauses. It means imagining a flourishing society for all people and committing to the work of building public infrastructure to promote that flourishing.

Q: You come from very different disciplines, with a shared focus on justice and equity. How did working with one another enhance your thinking and, as a result, sharpen the final version of the book?

Keisha: Adam and I collaborated on a number of projects in the past few years. In summer 2020 we wrote about the potential impact of COVID-19 on public education in North Carolina, along with Lauren Fox and Ashley Kazouh at the North Carolina Public School Forum. We led a Duke Bass Connections project, along with Jonas Swartz and Evan Myers in Obstetrics and Gynecology, on college students’ access to reproductive healthcare during the pandemic. In 2022, we both contributed chapters to The Pandemic Divide, a book that sought to capture the ways COVID-19 magnified existing inequalities in major areas of American life.

We have a good balance in our collaborations and we each bring different skills. One of my major projects in recent years explored effects at the intersection of race, religion, and health, and before this, Adam wrote a book about the radical, ethical challenge of James Baldwin’s writings. So even though we’ve studied different academic disciplines, but our interests and intellectual energies overlap. Suffice to say, we always have a lot to talk about.

Adam: On that point of balance: In economics research (and other disciplines), the first author is usually the leader of the project and the one who shepherds the work to completion. That was my role here—drafting material, outlining the structure and aims, weaving the pieces together, and chasing down every last citation. But the book is ours because of what Keisha brought to every step: deep knowledge across multiple areas of research, precision with language and argument, and an abiding commitment to the importance of making a better world for everyone by making a better world for people facing forces of ableism, racism, and misogyny.

Keisha’s contributions are especially important in two areas of the book. First is the connection between disability justice and intersectionality, a relationship that one of the anonymous peer reviewers flagged as needing more clarity. Keisha’s research—especially in the context of Black women’s health and educational outcomes—was essential to deepening and strengthening those parts of the text. Second is the material on quantitative research methods. As a social scientist, Keisha brought a level of rigor and care to the discussion of statistical research that I (quite obviously) couldn’t have provided alone. She is remarkably skilled at navigating the tricky terrain of numbers without flattening the complexity of people’s lived experiences.

Q: What books, articles, or ideas significantly influenced your thinking or deepened your passion for this work?

Keisha: We’ve already mentioned the impact that Black disabled activists and organizers had on our work, so to this question I’ll point more to scholarly influences. A special issue of Gender & Society in 2019 contained two articles that were invaluable to our thinking about disability and inequality: one by Angel Love Miles that outlined a feminist intersectional disability framework and another by Moya Bailey and Izetta Autumn Mobley that developed a Black feminist disability framework. Additionally, Sami Schalk’s Black Disability Politics was released in 2022 and is an absolute must-read on these topics. While we started working on Stratification Economics and Disability Justice well before Black Disability Politics was published, it was tremendously helpful during the final major revision of the manuscript